Mass violence and looting in African American, Mexican American and Puerto Rican American communities during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and 1970s — including the 1967 riots in most major U.S. cities that led to more than 100 deaths and the 1968 riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. — often targeted fire fighters, injuring and, in some cases, killing them. Buildings burned, there was wholesale looting and innocent bystanders, as well as responding fire fighters and police, were attacked.

An article in the Oakland, California-based Tribune stated: “As incredible as it sounds, some firemen in various parts of the country, including California and the Bay Area, have been on the receiving end of much abuse in recent months while doing nothing more than attempting to get to fires or put them out.”

An editorial by IAFF President William D. Buck in a 1967 issue of the International Fire Fighter titled, “The Terrible Summer of 1967,” read: “Fire fighters in the United States will always remember, with both sadness and bitterness, this terrible summer of 1967. It was the summer of the ugly city riots. And our men were on the unprotected frontlines. There is no need here to recount the highlights. In city after city, our firefighting services were the targets of violence — of rocks and stones, of molotov cocktails, of gun fires and clubbings. Fire fighters in the line of duty were killed and injured … injured by the scores of hundreds.”

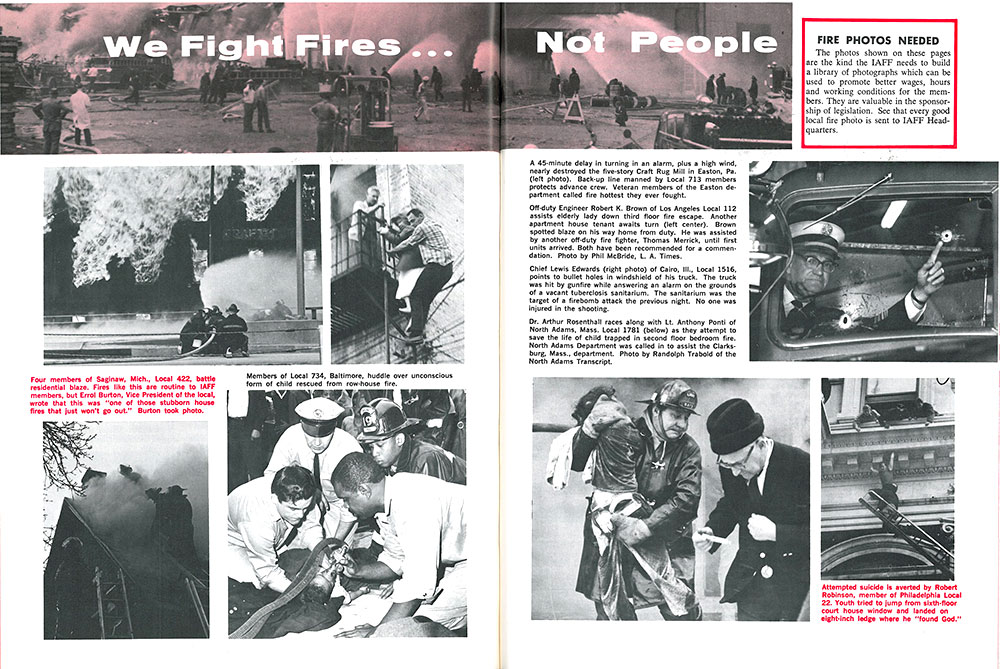

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson and mayors of major cities appointed a commission of leading citizens to investigate the cause of the uprisings. The IAFF started its own public relations campaign released to U.S. affiliates with the theme, “Do Not Fight Your Fire Fighter, He Is Your Best Friend.” The campaign is later shown as a photo spread in the magazine titled, “Fire Fighters Fight Fires, Not People.”

Various state affiliates took matters into their own hands. The Professional Fire Fighters of Wisconsin passed a resolution calling on the governor to appoint a committee to study the legal rights of fire fighters and how to best protect them while performing their duties under riot conditions. Rigorous ordinances were passed in Cincinnati for attacking the city’s fire fighters. In 1969, Allentown, PA Local 302 joined police in a new pilot program designed to improve relations with minority groups.

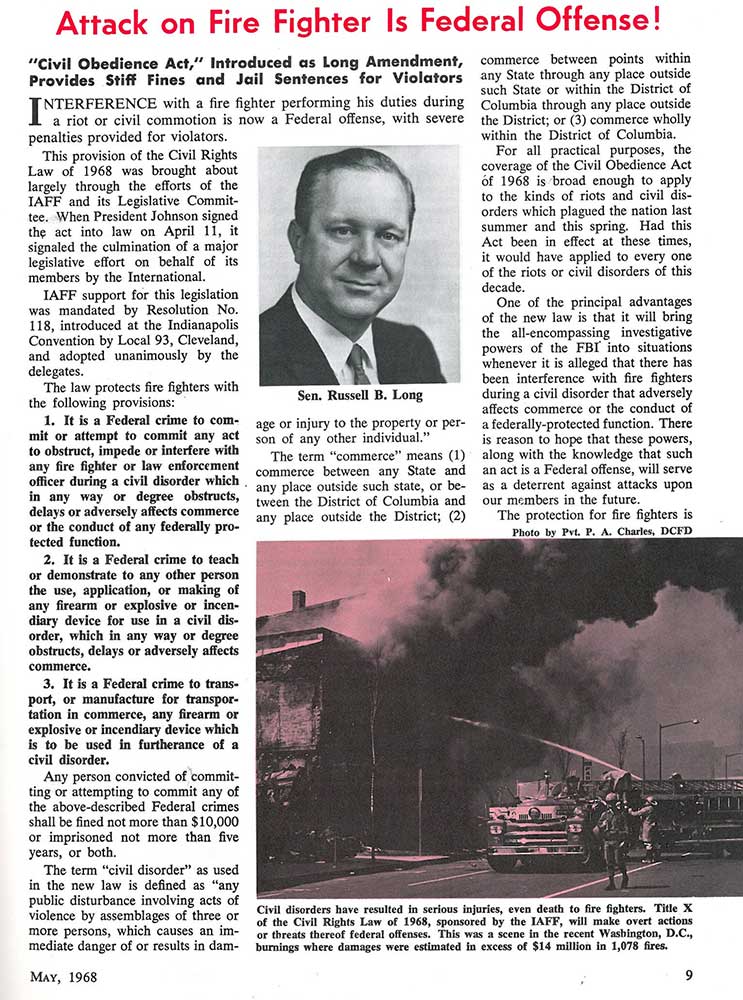

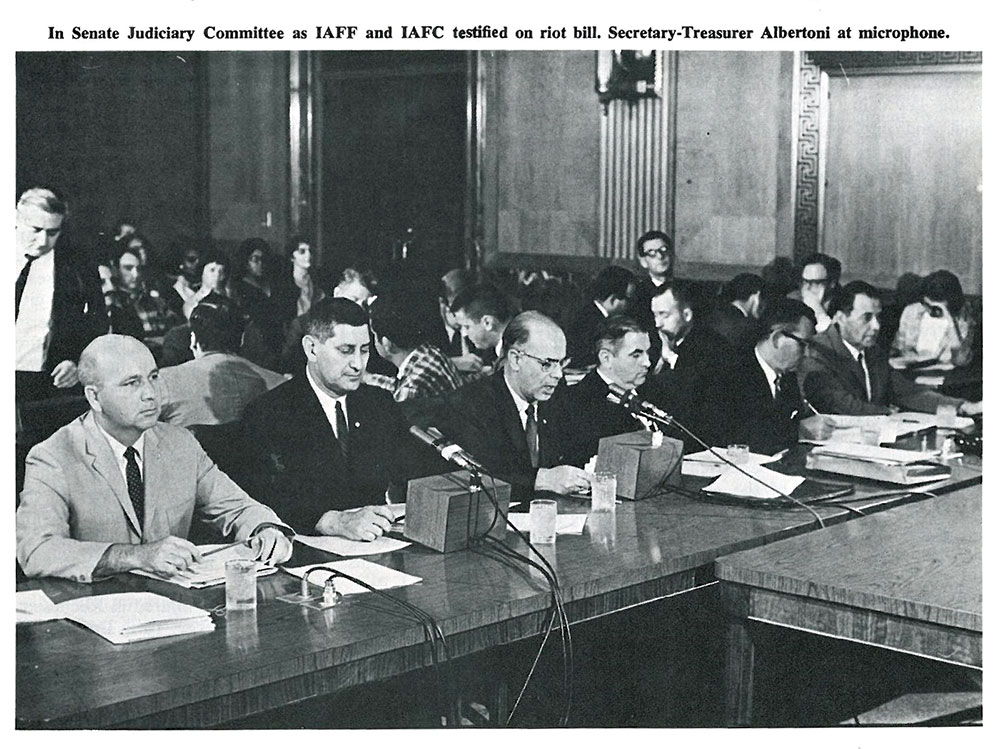

After the riots in 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Congress made it a federal crime to interfere with a fire fighter or law enforcement officer during a riot or civil disorder.

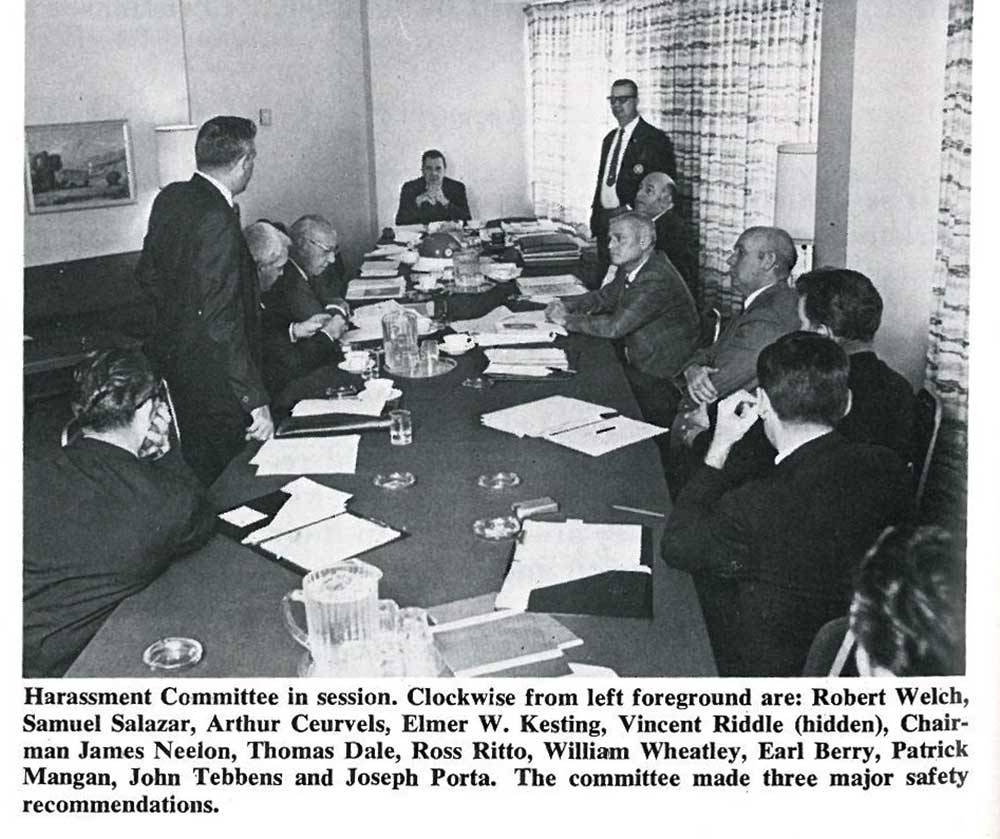

At the IAFF Convention in Toronto, Canada, in 1968, a motion was made from the floor that “a committee of 13 be appointed from cities where harassment of fire fighters has occurred for the purpose of presenting to the Executive Board a policy of protection of fire fighters during such harassments.”

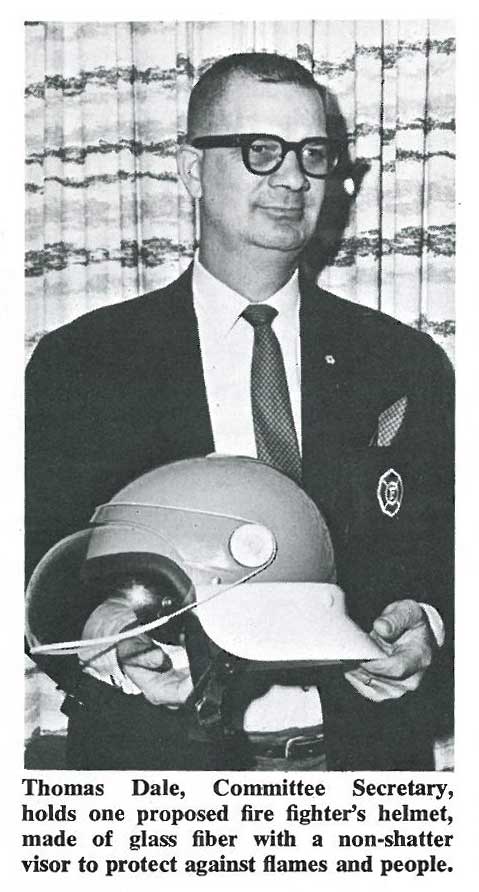

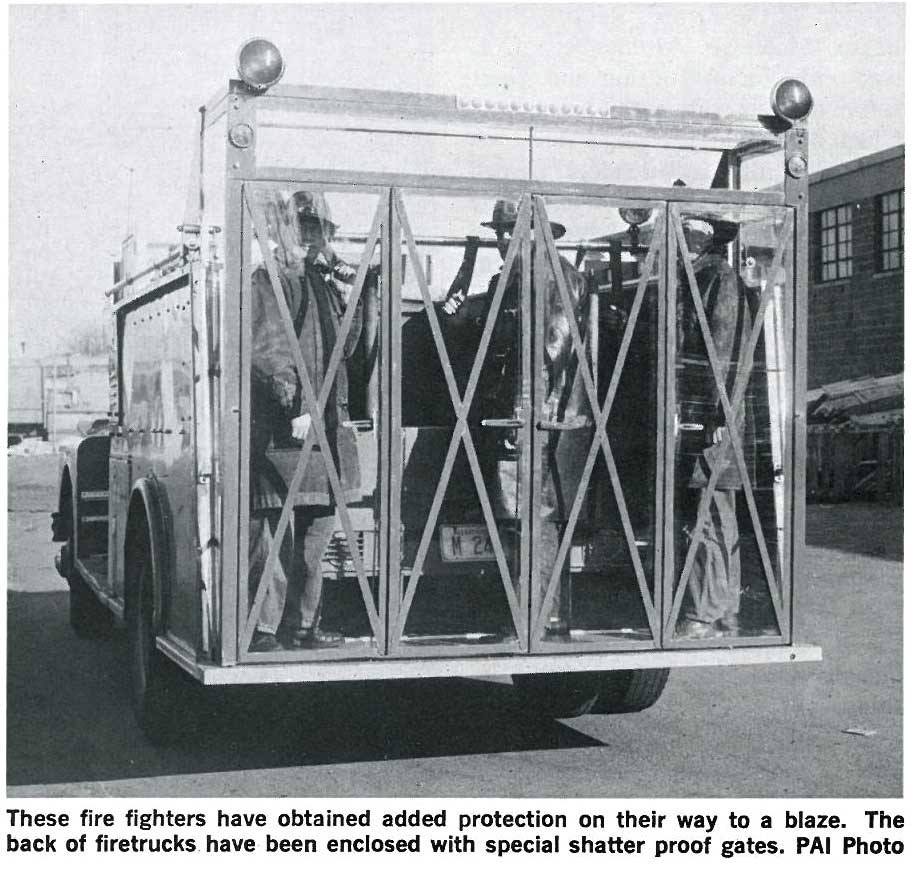

The Committee on Harassment and Protection of Fire Fighters brought forth many important policy recommendations for fire fighters under riot conditions, including the proposal that fire fighters should have protective shields and devices on all pieces of apparatus, and that fire fighters must not carry guns or other combat weapons to fires.

In 1969, the problem had not abated. In fact, in big cities – such as Philadelphia – fire departments installed bullet-proof plastic bubbles to protect exposed tillermen on ladder trucks. In 1970, it was reported that more than 600 fire fighters had been injured during civil disorders over the past three years.